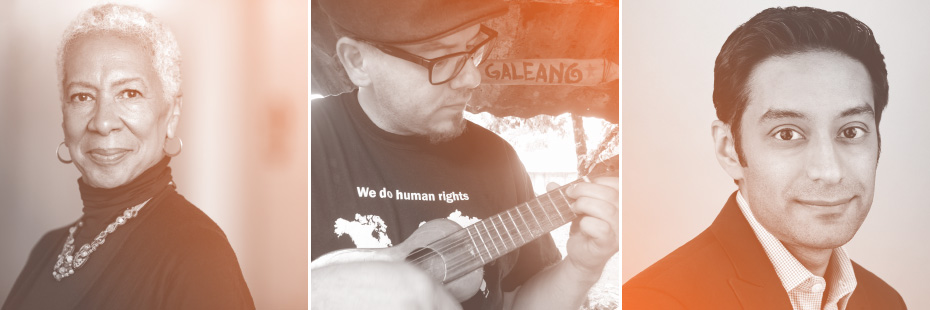

Open Borders with Roberto Corona and Farhad Manjoo

Host Angela Glover Blackwell in conversation with Roberto Corona and Farhad Manjoo

The United States once had open borders. Migrants from all over the world would arrive fleeing war, escaping poverty and seeking opportunity. Open borders made our country strong. But many Americans today are horrified — or frightened — by the idea of “open borders.” Harsh new immigration policies are making it more difficult than ever to come to the U.S. or even ask for asylum. Nevertheless, violence, oppression, poverty, desperation, and hope continue to drive migrants to our borders. Last year, more than 1,000 migrants from Central America gathered near the border of Guatemala and Mexico to travel north in search of asylum.

Radical Imagination host Angela Glover Blackwell sits down with Roberto Corona, founder of People Without Borders, an organization that assisted this refugee caravan. We also hear from New York Times Columnist Farhad Manjoo, who has called for open borders.

Angela Glover Blackwell (AGB): 00:04 Welcome to the very first episode of the radical imagination podcast where we dive into the stories and solutions that are fueling change. I'm your host Angela Glover Blackwell. In every episode on the show, we're going to look at a specific problem in our society and some of the radical ideas that are being dreamnt up and tested to answer those challenges. Today we bring up open borders, a concept that was once nothing out of the ordinary people moving freely, searching for opportunities, looking to improve their lives, but what would a world with open borders look like today at a time when restrictions on migrant flow in places like Europe and the U.S. are only intensifying and becoming so politicized.

news clip: 00:52 Anti-immigration sentiment is rising.

news clip: 00:55 The patriotic Europeans against the Islamisation of the West wants to curb immigration and accuses authorities of not enforcing existing immigration laws. Powerful scenes at rallies against the Trump administration's zero tolerance policy and the separation of children from their parents.

AGB: 01:11 Last year, more than a thousand migrants, most of them women and children fleeing violence in Central America gathered at the Guatemala, Mexico border to form a caravan. Collectively, they set off on a 2000 mile journey north to the U.S. Mexico border. It's a group called, when you translate it, a world without borders or people without borders. They're marching to the U.S. border cause they want in and they want to make a statement. At the time, the U.S. nonprofit Pueblo Sin Fronteras or "People without Borders" drew attention to their plight and coached them on how to exercise their legal right to ask for asylum. As the caravan grew bigger than even organized as expected, the U.S. media began to pay close attention and so did authorities. This group headed to the border, we don't know when they may arrive. Some are seeking asylum, some say they want to sneak over the border

AGB: 02:02 How will the border patrol react to this group of 1200 approaching the border eventually. As they reached the border, the caravan fragmented into smaller groups. Some made it through, others were detained, separated from their children and deported. Many are still in Mexican shelters waiting to ask for asylum. Today facing more obstacles and vitriol than ever before, migrants continue to head north and they're not just coming from Central America, they're coming from all over the world. Roberto Corona is the founder of Pueblo Sin Fronteras. He joins us from San Diego, California to talk about open borders, his organization, and the migrant caravans. Roberto, welcome to Radical Imagination. The idea of open borders tends to make a lot of people angry and frightened when they first hear about it, and many people think it represents lawlessness or anarchy. How did you happen to come up with that name: Pueblo Sin Fronteras, "People Without Borders," for your organization?

Roberto Corona (RC): That philosophy of 'sin fronteras,' which means 'without borders' is a very old concept that we in the Americas have, so many of the people participating in Pueblos Sin Fronteras also had strong roots from indigenous communities. So when we were talking about the name, one person in the community mentioned, sometimes we are afraid of the other person and we put a barrier between you and the other person because it's different from you. So that was the beginning of Pueblos Sin Fronteras, it was about breaking those barriers that are inside yourself now. And then, the physical border also comes from going back to our roots that our ancestors, they didn't have borders exactly, no.

AGB: I was going to ask, as you look at the history of the United States, people probably think that this is a very foreign concept, the idea of without borders, but is it foreign?

RC: I don't think it's foreign for the United States. We had open boarders. About 200 years ago, we needed labor, we needed hands to build New York and Chicago, so we opened borders and we put the Statue of Liberty welcoming everybody. It was during the second World War that the U.S. did enhance, and the bracero program came to exist.

news clip: Los braceros are a necessary supplement to our domestic crews. In Spanish, 'braceros' means a man who works with arms and hands, but in American lingo they are called lifesavers.

RC: And they start sending people to Mexico to hire workers and they start working in the U.S., picking the crops and building the United States. So through the history of the United States, we open borders when we need hands, we close the borders because political gain, the president also talking tough about immigration, pointed to that caravan of about 1500 Honduran nationals who are making their way through Mexico. President tweeting quote, "Mexico has the absolute power not to let these large caravans of people into their country. They must stop..." When we made the first caravan, nobody heard about it--only in Mexico. It was until the third caravan that Mr. Trump made a tweet and then everybody started seeing or looking at the migrants coming from Central America. It didn't start last year, it has been there for years.

AGB: Well, let's go back and tell that story. How did the idea of the first caravan come about?

RC: Well, it's something that I think needs to be clear is that we didn't organize the caravan, we facilitate information for the people stuck in the south part of Mexico, in Choapas, that were asylum seekers. They were not receiving proper help. So our role as human rights advocates, it was to educate them about their rights, in Mexico, not in the U.S. yet. These are your rights in Mexico. You have the right to ask for asylum, but they were denying asylum. And there was something happening already in Mexico called the via crucis, 'the way of the cross'.

RC: It needs something that local organizers and human rights advocates, they use popular religiosity to make a statement in Mexico, that they were just like Jesus, tied to the cross, being crucified in Mexico.

RC: So we said, okay, we can participate in the via crucis, we go and educate them about their rights as asylum seekers. So the idea was to do the via crucis' from Choapas, the south end border with Guatemala to Mexico City, and then, all of those who wanted to apply for asylum in the U.S., they could come and try. Everything that we're doing is by the law, international law, local law in Mexico, and the U.S. And also, we in fact tried to discourage them.

RC: Has no defense against cartels that extort vulnerable immigrants. Many are robbed, kidnapped, killed and still...

RC: It's terrible what they go through Mexico, organ trafficking. They have found mass graves with migrants with no organs, women that are taken for human trafficking. They use the migrants for drug trafficking. So it's a big business also for the organized crime in Mexico. So the idea and the via crucis was, okay, we need to denounce human rights violations in Central America, in Mexico, at the border, in the United States, because we are also violating human rights in the detention centers. We have reports of people being abused in the detention center. So we told these people, these are the risks that you are taking by going to the port of entry and asking for asylum. You need to really have a case. Otherwise you come into the United States, you will be put in a detention center, and then you will be deported if you don't have a strong case. So we just facilitate spaces for them to organize themselves.

AGB: An element that is often overlooked in the coverage of Central American immigrants coming to the United States is the role of the U.S. itself in driving so many to travel north. Looking back, give us some background on U.S. foreign policy in the region.

RC: Yeah, I heard from a friend this analogy, we have burned our neighbors home and the only thing that they are doing is coming and asking for a little space in our place while they fix their lives and what he meant by "we have burned their home" is that yes, our foreign policies in Central America, specifically, have been the engine or the catalyst to start these migration. And it started in the 80s when the wars in El Salvador and Guatemala, in Central America.

RC:The people of El Salvador are caught in a web of terror, has U.S. aid contributed to peace and democracy in El Salvador or merely strengthened a military regime that wages low-intensity warfare on its own citizens.

RC: We see the interventions of the U.S. foreign policies in El Salvador. I have a friend, he's from El Salvador, and he saw the war and he questioned this. How come the United States is trying to help us, but are sending arms and helicopters that are killing us.

RC: I think that the roots of migration, I think it has to do with that human instinct that we have to survive. For millennia we have been migrating. We need to eat, we need shelter, we need to be healthy, so if we do not have that where we live or safety, we have to go. We go somewhere else and try to find it.

AGB: Many people in the U.S., including members of the government, have accused people without borders of fostering illegal immigration because of the role of the caravans. How do you respond to those critics? Yeah, we're doing a humanitarian work and we are not doing anything illegal, we're just accompanying people. We are not afraid because we're not doing anything wrong. We are using human rights and we are putting them into practice. Right now we are not accompanying with the new people coming. We need to see what's going on. We are trying to understand better and the ways that we can help, and when they're in detention centers we also try to find organizations that can help them. We are a very small collective and we don't have the resources, even though people have said that we received money, I don't know from who -- we have nothing. What we have is friends and people of good faith. They want to help the migrants and the asylum seekers. We have also received critiques from other organizations. "Look what you are doing," and it's not that we are doing this. This is happening from long ago and this is going to continue happening, and if you put one or two or three walls,

AGB: if they see that the United States is a better place, they will continue coming here. It could be through the ocean or many ways. Roberto, I am so moved as I hear about your efforts and the efforts of People Without Borders to really make sure that the journey is safe and to open up the conversation about borders. People who do the kind of work that you do are often tapping their inner strength to be able to do it, and I think that people are really bringing their superpower to this work. When you think about it, Roberto, what's your superpower?

RC: My superpower, I think is to bring people together, it's precisely building bridges among human beings. I think I'm able to see the common dreams and just create the spaces so people come together and dream together and do something about it.

AGB: 12:55 Roberto, thank you for speaking with us. Thank you for having me. Roberto Corona is the founder of Pueblos Sin Fronteras or People Without Borders, from San Diego, California. Coming up on Radical imagination, we hear from New York Times columnist Farhad Manjoo, who earlier this year wrote an op-ed calling for open borders. Stay with us, more when we come back.

PolicyLink: 13:35 Are you someone who wants to create a society where all can participate in prosper? Visit our website at radicalimagination.us to take action and connect with campaigns and organizations around issues covered by this podcast. It's crucial that we get support to continue to lift up stories and solutions to address our most pressing problems. To do this, we need you to tell your friends and family about Radical Imagination. Ask them to subscribe, share, and comment on their chosen podcast platform. Like what you've heard today, tell us about it. Go to apple podcasts to rate and review Radical Imagination, and thank you.

AGB: 14:21 And we're back. Earlier we heard from Roberto Corona who founded the organization that helps Central American migrants make a safer journey to the U.S. border. I'm now joined by Farhad Manjoo. He's an opinion columnist with the New York Times and he joins us to talk about an op-ed he wrote this year, titled, "There's Nothing Wrong With Open Borders." Farhad, welcome to Radical Imagination. Hi, good to be here. So your column was published in The New York Times last January. The title itself must have been enough to get some interesting responses. What type of reaction did you get?

Farhad Manjoo (FM): I think the reaction was almost all negative. There was a small number of people in the comments I think and you know, in email, mostly immigrants themselves who agreed with me about borders because there was a faction of I think Libertarians who agreed with me. But for the most part, and I expected this, uh, pretty much everyone disagreed with my idea. They thought it was unworkable. And at a more fundamental level, un-American, which I totally disagree with.

AGB: 15:28 Given that you anticipated that you were going to get a negative reaction, what made you decide to write the article in the first place?

FM: 15:35 Well, I noticed that we'd been talking a lot in the United States over the past few years because of the term presidency about immigration, the Republican Party and the Trump position seemed very clear to me. I think that it's kind of obvious that the president doesn't like immigrants, wants fewer of them. And, you know, while I completely disagree with that policy, I understand what his position is. And I found myself trying to figure out what the position of the Democratic Party was, and I couldn't really, because if you go back 10 years or more, you can find democrats arguing for the kind of border security that republicans now do. It's sort of been an orthodoxy among democrats that we'd have this idea of secure borders and that there was nothing wrong with increasing our border apparatus and keeping people out. And to me, that seemed both wishy washy and kind of not really what I think a lot of people feel. And also just too close to the republican position. And as an immigrant, you know, I've always felt differently, which is that I somehow luckily won this kind of amazing lottery. I'm not the actual immigration lottery, but kind of the lottery in life to come to the United States when my parents did in the 1980s and that has made all the difference in my life. And I don't see a moral reason why anyone else in the world shouldn't get the same opportunity.

AGB: 16:56 Well, what's interesting about the negative reaction and almost the universal nature of it, is that people don't really seem to know the history of this country. If you look back at history, open borders are nothing new, why do you think the idea of open borders scares so many people?

FM: 17:13 That was the fundamental nature of my inquiry into this, which is, if you understand the history of immigration in the United States, you sort of have to be okay with open borders, or you have to be okay with the idea that, you know, at least in the early days, open borders was the way we understood society. There were few restrictions on anyone coming into the United States. There were restrictions on what it meant to be a citizen and the sort of the rights that different people had in the country. But simply coming here and living here legally was, you know, not a question of real debate until the late 1800's and then really in the early 1900's when there were waves of immigrants. And you know, most people who are in the United States today can tie their own ancestry to the period of open borders. They're here because of open borders. And I think we made a fundamental mistake when we decided to close the borders, and I think we'd be better off if we had, you know, kept that same or something more along the lines of the immigration policy that we had in the early part of this country.

AGB: 18:21 So it may be that there were political or economic reasons or other reasons for closing those borders when that started to happen. What people say now is that they think that it's dangerous to have open borders. They think that it will ruin the economy or in some way they talk about it having a negative impact on native workers. What does the evidence say about those fears?

FM: 18:45 It does make sense that if you allow an influx of people to come in, you will affect job markets in the United States. You might affect the markets for lower-skilled workers. Although you know, one way to address that is to pass protections for lower-skilled workers. You can have a minimum wage, you can have health protections. A lot of people come into the United States every day from all around the world. We already have, you know, essentially open borders for all of Europe. We have agreements with many countries in the world that their citizens can come here without needing a visa, without needing, you know, much of a background check. The fear comes in because it's greatly influenced by people's ideas of race and culture and how areas around them are going to change. If you let a lot of other people in, and I understand people are fearful of change, but that's America. I mean that's the basis of this country. Every part of America is very different from what it was when we first started and change and innovation and progress and sort of the underlying idea here. And if you sort of start to close yourself off to change, you close yourself off to, you know, all the amazing possibilities that the rest of the world can bring us.

AGB: 20:06 It's so refreshing to hear you talk about amazing possibilities. I think that one of the problems that we have is that people can't envision what it would be like. What might the U.S. with open borders look like and how might it act?

FM: 20:21 There are technically political borders between California and Oregon or California and Nevada. We pass state borders all the time. People in different parts of this country are very different from each other, but we allow them to go freely within the country or think about the European Union. People move freely within the European Union. There is obviously some angst about that, but for the most part it works.

AGB: 20:46 I want return to when you were talking about how you happened to come to the United States in your piece, you talked about your family coming from South Africa, having had that experience, how do you individually relate to the rest of immigrants who were able to come and pursue their dreams in the U.S. or to those who are struggling to try to do so today?

FM: 21:05 Yeah, I mean I think that is the key reason that I think this way about borders and that, you know, native born people don't, which is that I crossed the border and I have not much more affinity for the people around me here in the United States than I do for the people that I left back in South Africa. They all to me seem like people, and it just seems terribly unfair to me that somebody who you know is back in South Africa where I'm from or anywhere else has some dream of coming to live in the United States in expanding their opportunities here and is denied that on the basis of fictional lines in people's heads.

FM: 21:50 What are some of the economic arguments that support open borders? You know, if you look at the data for who creates companies, who run some of the most innovative companies in the world, they're often immigrants and you know, a large portion of Fortune 500 companies were created, founded by, people who were not native born Americans. And It stands to reason that if you sort of open up opportunity for the best people in the world, that you will get those people and they will create great things here. And you know, I spent a lot of my career as a journalist covering silicon valley and those companies, the companies that are here, just sort of wouldn't work without immigrants.

AGB: 22:33 And while economics is extremely important to this conversation, you write about a deeper moral argument that tends to be less present in the immigration debate. The moral case for open borders.

FM: 22:45 I don't think that the ideas of freedom that are outlined in our founding documents, I don't think those ideas work with the idea of borders. I mean we have in the Declaration of Independence, the idea that all people are created equally, and it's not just people born within this part of the world. It's everyone.

AGB: 23:07 And in your column, you pushed even deeper on this moral question, quoting Reece Jones, a professor of geography at the University of Hawaii stating that quote, "when you start to think about it, a system of closed borders begins to feel very much like a system of feudal privilege. It's the same idea that there's some sort of hereditary right to privilege based on where you were born. "

FM: 23:32 It is feudal. We, you know, have long moved away from the idea, in the United States that the place you were born in should decide your future. But we cling to it only in this idea of national borders. This idea that, you know, if you're born on this feudal land then you belong to this lord and have this kind of right, and if you're born elsewhere, you have another kind of right that doesn't sort of mesh with our ideas of universal freedom.

AGB: 24:03 Why do you think that this is a political opportunity to push this really quite radical idea forward?

FM: 24:12 You know, as I said, it's a moral policy. It's the moral position. And I also think it could be the winning political position for a couple of reasons. First, open borders has the advantage of being a clear policy. And I also think that in the long run, borders are going to start to seem more and more like artificial inventions and they will play sort of less of a role in our lives. You know, I mentioned how tech companies already have huge workforces outside of the United States and that's going to be more and more true for all kinds of companies because technology will allow that, you know, it will be possible for workers in Mexico and China to operate manufacturing robots here in the United States through things like virtual reality or better internet connections. It will be possible for us to have, you know, greater social connections with people outside of the United States. One of the most popular social networks for young people today, TikTok, is created in China by Chinese developers and it's popular here in the United States, and I think those kinds of cross-cultural connections are going to make borders seem less and less like a logical part of society. And so I imagine, you know, one of the political arguments here is that being for borders is going to start to seem like being on the wrong side of history.

AGB: 25:36 So I have been reading your columns, and I love the way that you pull out of what has been nagging in some people's minds and you put it front and center, you really know how to bring interesting issues into relief and to move an argument so that people can see it differently. When you reflect on it, what's your superpower?

FM: 25:58 In our kind of public debate right now, because of social networks because of cable TV, we often get kind of closed in our received wisdom I think. And it's difficult to kind of step out of it. And I think one of the things I try to do in my column is just kind of question the received wisdom of people on sort of all political sides. And I think there's an appetite for that in the world today because a lot of sort of the takes we get in media often are just very comfortable for people. You know, for Republicans there's a certain view, and for democrats there's a certain view, and people don't often want to step out of their comfort zones. And so, I often begin with that question of, you know, what are people missing? What's an idea? That's a good idea that no one is saying because it's a little bit of an uncomfortable idea.

AGB: Farhad, thank you for speaking with us today. Thanks so much.

AGB:: 26:59 Farhad Manjoo is an opinion columnist with the New York Times.

AGB: 27:12 I want to take a second and talk about the concept of the podcast. Radical Imagination. We're at a time in which the demographics are changing, in which people who really want to see a fully inclusive society are moving into positions of leadership. And yet we're still tinkering around the edges of institutions and systems that were never designed to make sure that everybody could participate, prosper, and reach their full potential. It's going take radical imagination to be able to design those systems and to identify what it is that everybody can contribute for us to make sure that those systems work for all.

AGB: 27:53 Sometimes compassionate action is the most radical way to defy state sponsored bigotry and oppression. The underground railroad is an inspiring example. It established secret routes and safe houses, so Black slaves could escape to free states. The migrant caravans follow this legacy like slavery, our immigration policy is rooted in racism. It shuts out brown people, rips apart Brown families, and locks brown children in cages. Open borders would solve these problems, but until that happens, we need acts of resistance. The caravans may defy current policy, but they uphold our nation's most fundamental value that all who seek a better life are welcome to come in.

AGB: 28:48 Radical Imagination was produced by the Futuro Studios for PolicyLink. The Futuro Studios team includes Marlon Bishop, Andrés Caballero, Ruxandra Guidi, Stephanie Lebow, and Jeanne Montalvo. The PolicyLink team includes Rachel Gichinga, Glenda Johnson, Fran Smith, Jacob Goolkasian, and Milly Hawk Daniel. Our theme music was composed by Taka Yusuzawa and Alex Suguira. I'm your host, Angela Glover Blackwell. Join us again next time, and in the meantime, you can find us online at radicalimagination.us. Remember to subscribe and share. Next time on Radical Imagination, the call for police abolition, and a deeper look at what it actually means.

Angela Glover Blackwell, Host.

Radical Imagination was produced by the Futuro Studios for PolicyLink.

The Futuro Studios team includes Marlon Bishop, Andrés Caballero, Ruxandra Guidi, Stephanie Lebow, and Jeanne Montalvo.

The PolicyLink team includes Rachel Gichinga, Glenda Johnson, Fran Smith, Jacob Goolkasian, and Milly Hawk Daniel.

Our theme music was composed by Taka Yusuzawa and Alex Suguira.

Radical Imagination podcast is powered by PolicyLink.

There’s Nothing Wrong With Open Borders: Why a brave Democrat should make the case for vastly expanding immigration. By Farhad Manjoo

The internet expands the bounds of acceptable discourse, so ideas considered out of bounds not long ago now rocket toward widespread acceptability. See: cannabis legalization, government-run health care, white nationalism and, of course, the flat-earthers.

Yet there’s one political shore that remains stubbornly beyond the horizon. It’s an idea almost nobody in mainstream politics will address, other than to hurl the label as a bloody cudgel.

I’m talking about opening up America’s borders to everyone who wants to move here.