Land Back

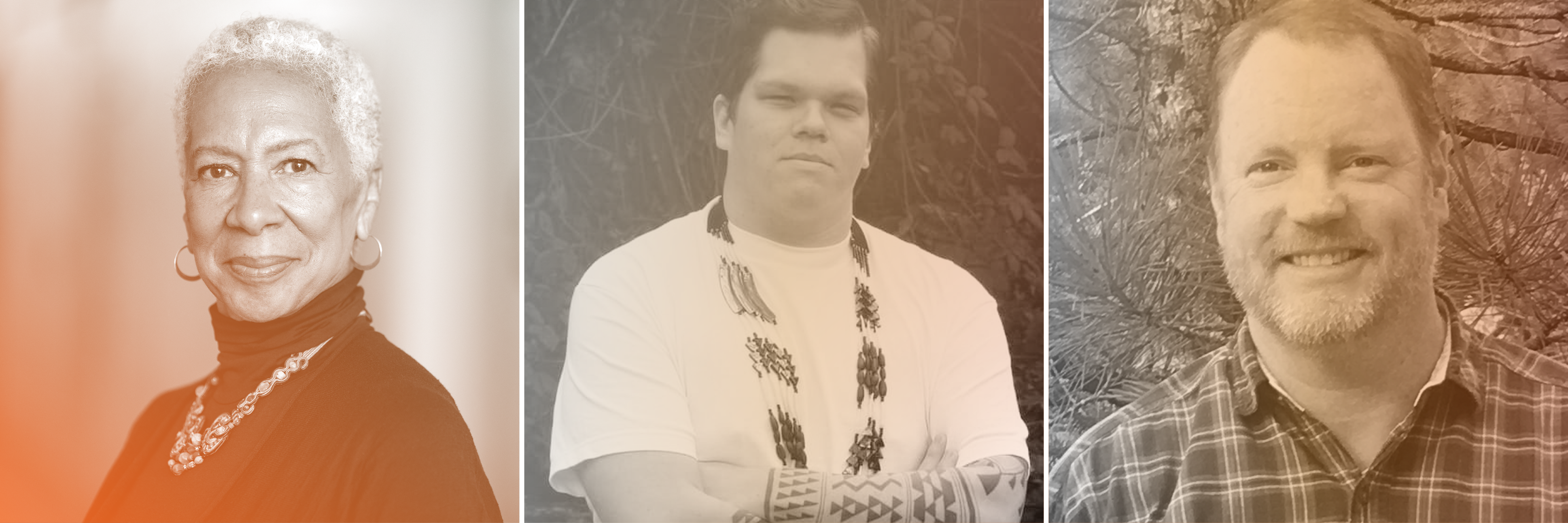

Angela Glover Blackwell in conversation with Clyde Prout III, chairman of the Colfax Todd’s Valley Consolidated Tribe in California and Jeff Darlington, the director of the Placer Land Trust.

Today on Radical Imagination, Clyde Prout III, chairman of the Colfax Todd’s Valley Consolidated Tribe in California, tells the remarkable story of how his tribe reclaimed land stolen by the government nearly half a century ago. Native people were violently displaced from their ancestral homelands throughout US history, as land was stolen and sold to private owners, made “public” in the name of preserving natural resources, or set aside for agriculture and recreation.

We’ll also hear from Jeff Darlington, the director of the Placer Land Trust, about the partnership that made it possible for the tribe to take back their land and restore it through traditional cultural and ecological knowledge.

Angela Glover Blackwell: 0:07

Welcome to the Radical Imagination podcast, where we dive into the stories and solutions that are fueling change. I'm your host, Angela Glover Blackwell. Throughout U.S. History, the government has been violently displacing native people from their ancestral homelands. Land was stolen from Native Americans and sold to private owners, made public to preserve beautiful natural resources, or set aside for agricultural or recreational use. In the early 20th century in California – a state that is currently home to over 700,000 Native people – the federal government established Rancherias, which laid the groundwork for tribes to establish reservations. Many of these rancheria reservations lasted only about half a century, and were re-stolen by government through a series of California rancheria termination acts in the 1950s and 60's.

Speaker 2: 1:08

Secretary of the Interior Walter Hickel, who is in charge of Indian affairs, was set out along with Vice President Agnew to reassure the Indians that the "Great White Father" will provide for them.

Angela Glover Blackwell: 1:21

Over the next five decades, many rancherias returned into public land trusts that remain undeveloped and uninhabited to this day. Like the Placer Land Trust in Northern California. Native leaders and environmentalists are figuring out ways to work together to give stolen land back, which many hope will begin along overdue healing process. On today's episode, we'll talk with Jeff Darlington from the Placer Land Trust about how a group of conservationists returned protected land to its original native stewards. But first let's hear from Clyde Prout III, the chairman of the Colfax-Todds Valley Consolidated Tribe. Nearly 60 years, after the last time the government stole his tribe's land, he's working with the Placer land trust to get it back. Chairman Prout, welcome to Radical Imagination. Can you introduce yourself and your ancestral Nisenan Maidu language ,

Chairman Clyde Prout III: 2:19

Hūma’ kani, Clyde Prout [ancestral Niesnan Maidu] Colfax-Todds Valley Consolidated Tribe. [ancestral Niesnan Maidu]. I am Clyde Prout. I am Nisenan and I am the chairman of the Colfax-Todds Valley Consolidated Tribe.

Angela Glover Blackwell: 2:32

Thank you so much for being here to talk about what's going on in your community. Could you tell us more about the Colfax-Todds Valley Consolidated Tribe and your history?

Chairman Clyde Prout III: 2:41

The Colfax-Todds Valley Consolidated Tribe is the formal government name of what is the Colfax Rancheria. Most of the Plains culture or certain parts of California have reservations. We have what were called rancherias. The Colfax Rancheria is descendant of Nisenan, Maidu and Miwok people, with a little bit of Washoe coming over the hill. For generations, we've lived in Placer County. For generations, this has been home. In the early 1900's, there was a piece of property that was purchased for the homeless landless Indians and Colfax , which became the Colfax rancheria. So many families applied for allotment through the Bureau of Indian affairs, but the bureau wasn't offering to help – like they should be. My grandma, she wrote two letters to the Bureau of Indian affairs, the first time asking for allotment, and the second time asking for allotment. And at this time she already had six children and was struggling to make ends meet already at that time. And they told her that she could move there, but they're in the process of trying to sell. Once 64 act happened and the rancheria was sold, when the land was terminated, then we became an unrestored tribe, meaning that we didn't have an actual land base, we weren't a tribe in the eyes of the government anymore. Basically we didn't have rights anymore.

Angela Glover Blackwell: 4:12

How did this affect you growing up?

Chairman Clyde Prout III: 4:15

My family for years since the post termination act, no one's ever owned a home. No one's ever lived in a solid place. When I was a kid, I remember my grandma had all these kinds of plants. She loved planting, but she never plant them into the ground, because we always had to move. And that was something that has always driven me is coming home. Having a place that you can go and do traditional things, medicine gathering, or even getting things, you know, to build ceremonial houses or even finding feathers for your dance regalia. It's been a dream for a long time. And when I realized was when I got older and started getting more involved, seriously, more involved with actual council and just wanting more and to have a place that's our own.

Angela Glover Blackwell: 4:59

You said the words Post Termination Act. So once the government stole the land that made up the Colfax Rancheria in their eyes, you no longer exist. And even though the status hasn't changed, now you have a formal government. When did you first found the Colfax Todds valley tribal council ?

Chairman Clyde Prout III: 5:18

So the first tribal council was established in March of 2000 . We just wanted more for our community actually being restored and being a government again, and being able to help give housing, education, better healthcare to our people. And it's been, it's been a long struggle

Angela Glover Blackwell: 5:35

And you are related to the first tribal chairman, right?

Chairman Clyde Prout III: 5:39

Yes, he is my uncle. <laugh>

Angela Glover Blackwell: 5:41

What drove you to get involved?

Chairman Clyde Prout III: 5:44

When I was a child, I was in council meetings, sitting on the sideline and kind of playing, but listening at the same time. So I've seen the vision and seen what everyone, everyone wanted to achieve. In 2009, I joined as the member at large and, you know, just tried to help where I could. And then in 2016, I actually ran for Tribal Chairman and got the position.

Angela Glover Blackwell: 6:13

When first elected, you were motivated by bringing visibility to your tribe, but gradually your focus is chairman shifted to obtaining restored status. Can you talk a little bit about what that means and explain being federally restored versus being federally recognized?

Chairman Clyde Prout III: 6:30

You'll hear people say unrecognized tribe. I don't like to use the word 'unrecognized,' because I know who I am as a native person. So I say unrestored

Angela Glover Blackwell: 6:46

When this land is officially transferred back to the tribe, will this help reposition you for restoration?

Chairman Clyde Prout III: 6:53

It definitely helps. It helps to show that we have, we're maintaining ourselves as a government. We're maintaining ourselves as a community and that all these other organizations that we are working with acknowledge us. And that's the biggest thing in challenging or petitioning the government for restoration, which is a whole conversation by itself. <laugh> but it gives a conversation of like we're acknowledging the community . These people recognize us .

Angela Glover Blackwell: 7:21

Why is it so important to restore status for native people?

Chairman Clyde Prout III: 7:25

So when your tribe is restored or the rancheria or whatever land base you're claiming is restored, the government now looks at you as a tribe. Now they actually will work with you on funding to help support your community. Whereas an unrecognized tribe, some people won't work with you, or they will not acknowledge you as a tribal government, which is why working with Placer Land Trust has been so amazing for us because it's an agency that recognizes us as a tribe and a tribal community. It also gives us another voice in saying that we're a tribal government.

Angela Glover Blackwell: 7:58

So how can this land transfer process help to actually preserve natural resources and help make native people more visible?

Chairman Clyde Prout III: 8:06

The goal is to give opportunity to teach other people about cultural maintenance and traditional specifically Nisenan Maidu Miwok practices of maintaining natural forest and fuel reduction. 100% of what we do as a community – if you look at our housing structures, if you look at how we dance, if you look at how anything that we have – it all comes from the land; it all comes from the earth. We give respects to the earth. You know, when we dance, at certain times of the season, it's usually, you know, times when harvest is about to come, you give offering, you give prayer. When we dance with certain skins or anything like that, it's because we're paying respect to that animal and giving prayers to that being, and giving acknowledgement to that life. Because we want that life to come back and keep coming and, you know, living together and just unison.

Now we're taking more than what you need and giving back. It also will open a discussion, I think, with other unrecognized tribes to talk to their actual local land trust, and maybe give them a voice and just saying 'they did it, we can do it too.' And we want to open a communication dialogue of working together and preservation and protecting our sacred sites and cultural practices. You know, actual forestry,

Angela Glover Blackwell: 9:30

Could this radical environmentalism be a blueprint for future land back initiatives across the country? What do you think?

Chairman Clyde Prout III: 9:38

Absolutely. I think this is a jumping point for people to just a framework of where people can see is like, this is how this was successfully done. Now, how can do this again. And again, and again, and again, tribes getting land back, especially unrestored tribes is something that isn't too common or that you hear of a lot. So it's, it's a big opportunity for the tribe and we're extremely grateful for everything. So we wanna very much give thanks just to Placer Land Trust, you know, do a actual formal signing . People can see the property offer songs that are of Nisenan Maidu language and gift some things to people just to show our appreciation. Something that we are actually really hoping for is to give the framework of how one unrecognized tribe can work with a land trust and make it successful. So that way, you know, unrestored tribes who are trying to maintain their actual homelands who have the ability to can.

Angela Glover Blackwell: 10:41

Chairman prout, thank you so much for talking with us.

Chairman Clyde Prout III: 10:44

Thank you for your time. I appreciate just having this opportunity to actually speak.

Angela Glover Blackwell: 10:50

Clyde Prout III is the chairman of the Colfax-Todds Valley Consolidated Tribe, which just reacquired a plot of stolen land from a public land trust. Stay with us. More when we come back. Jeff Darlington is the director of the Placer Land Trust, which recently returned a plot of publicly owned land to the Colfax-Todds Valley Consolidated Tribe. Jeff Darlington, welcome to Radical Imagination.

Jeff Darlington: 11:48

Thank you for having me. Great opportunity to tell our story.

Angela Glover Blackwell: 11:52

Could you give us some context about the Placer Land Trust and the reasons why it was created?

Jeff Darlington: 11:58

Yeah, the Placer Land Trust was formed in 1991 and it was a bunch of residents in the Roseville area here in Northern California that were seeing this county develop very rapidly. And it, Placer County has been one of the fastest growing counties , uh , in California since then. But they were concerned because they were seeing some of the natural open spaces get paved under. The land trust was formed like most land trusts– by local people looking to protect their little corner of the world. And as Placer County grows, we wanna make sure that some of the natural open spaces, working farms and ranches, historic lands, those are also protected. So that future generations get to enjoy this beautiful place.

Angela Glover Blackwell: 12:44

Tell me about the relationship between the Colfax-Todds Valley Consolidated Tribe, the Placer Land Trust and the land itself.

Jeff Darlington: 12:52

Conservation is a shared task. They obviously have the history on the land that greatly surpasses , uh , those current land owners that are here. But more importantly, perhaps to a partnership with the land trust is, they have a knowledge, a generational knowledge that we don't have. And that really translates to how do we take care of these lands once we acquire them? What state is the forest in? What state are the Oak Woodlands in? You know, are there invasive species that need to be managed? The land trust has standards and practices for managing land and our local tribes have their experience, their traditional ecological knowledge. And I think what's great about working with the tribe is we get to learn from each other. And what's great about this project is we get to learn from the land and from each other at the same time. This is part of a process for us, part of a relationship that we intend to be perpetual much like the protection of the property.

Angela Glover Blackwell: 13:51

I'd like to hear more. How did that first conversation about returning the land happen ?

Jeff Darlington: 13:57

Well, the first conversation was actually with Clyde's cousin, Travis. And we were, we were out at another property along the North Fork American river. It was about a year ago and the property we were visiting was probably about 15 miles downstream from the Gerjuoy preserve that we're talking about today. Well, we were there with members from actually three local tribes. It was the Colfax-Todds Valley Consolidated Tribe, the United Auburn Indian community, and the Wilton rancheria. And this was another property that we were looking at conserving, and we were asking the local tribes to help us assess it, you know, and help us learn about its cultural values and its history. And that's just part of our process. We wanna learn about the birds and the bees on the property, but we also wanna learn about, u h, you know, how the property has been used in the past and its importance to our local community, including our local, you know, indigenous community and our tribes. We're talking about all the things we want do and partner together. And, we were talking about the ger joy property and we said, well, that'd be a good one for us to work together on.

And, and you know, maybe do some joint management and Travis just said, well, what do you think about, you know, donating it to us, you know, or having, having us own it, that that might really be something that we won we'd be interested in because you know, it helps us show and demonstrate that we have standing here in this community when we, when we own and manage land. And I thought, huh, it's a pretty radical idea. I hadn't really thought of that before. I said, you know, that might be a possibility. We acquired the property in 2020 from Neil Gerjuoy. And we used funding from the state of California Wildlife Conservation Board to do that. And when we get grant funding from the state or many sources, you know, there's some restrictions that come with those, those grant funds. And so I needed to check with the wildlife conservation board and see, you know, is this even possible? How did this happen? Or why did it happen? They asked. They brought up the idea and we thought, you know, why not what's to stop us from doing this? The state has been very supportive.

Our funder has been very supportive. Uh, we have a pathway to transfer it. The transfer will go through the coil land Conservancy. The tribe's nonprofit that you know, is dedicated to land ownership and land protection. And they'll assume the grant conditions and they'll assume the responsibility of protecting the property and perpetuity and, and meeting those grant terms and perpetuity. Actually part of our agreement with the tribe is to spend three years doing joint monitoring and doing reporting to the state for three years at a minimum. So that, again, we can use that time to learn from each other in the land.

Angela Glover Blackwell: 16:45

Why is this partnership and returning the land to the Colfax-Todds Valley Consolidated Tribe the best thing for the land?

Jeff Darlington: 16:54

We'll be learning a lot from the tribe. They have a lot of knowledge that we don't. That's the beauty of, you know , uh , working together is that you get to leverage each other's strengths. So this property is a beautiful property. It overlooks the North Fork, American river, it's on a ridge. And if across the country, you know, what's California known for, well, unfortunately one of the things we're known for recently is these catastrophic wildfires. So managing our forest is really important. It's never been more important. It's gonna be more important tomorrow than it was yesterday. And so all the knowledge that we can apply to forest management , uh , to fuel load reduction, you know, using prescribed burns, but also using cultural burns . Clyde and , and the tribe have talked to us a bit about how they do that, which is different than say, you know, a large scale mechanical , uh , thinning. So there's lots of tools and approaches we can apply to management when we work together. So I think this property through this transfer is gonna get more love and more care by having the tribe own it and having us continue to work with them.

Angela Glover Blackwell: 18:02

And do you have plans to be able to share this so that the lessons that are being learned there in Placer County can inform other efforts because sometimes you hear about this in the context of tension between conservation and native stewardship, but you are actually finding something very different. How will others find out about this so that we can see replication and spreading?

Jeff Darlington: 18:26

That's a good question. First, let me just say about tension. I feel that tension in a , in a lot of our work there's tension between agriculture and habitat, there's tension between agriculture and recreation. There's tension between recreation and cultural preservation. Those are not mutually exclusive objectives. And that's really the word that we're trying to spread here. In terms of how can, what we're doing be replicated. I'll tell you I've learned so much from my land trust colleagues, and I hope to be able to share this model with them, from what I'm hearing from others in the land trust community. They're very interested in what we're doing and they're looking for ways to make it happen in their own regions.

Angela Glover Blackwell: 19:06

Could this radical environmentalism be a blueprint for future land back initiatives across the country? What do you think?

Jeff Darlington: 19:14

I think there'll be a dozen or so blueprints out there that land trust will use. And this will be one of them . This is land that was already protected by us using a specific set of , uh , guidelines from the state of California. The entity that we were working with. It's a state that granted us, the , the funds to protect the property in the first place is the California wildlife conservation board, big , uh , players in terms of state funding for conservation. And they said that we are the first ones to transfer land to a tribe that was previously purchased for conservation and encumbered it in that way. So there are other land back projects that have happened in California, but this is the first one that that agency has funded. That was protected. Not with any intent , uh, you know, back in 2020, we didn't have any intent to transfer this property. There are hundreds of projects that are like this project. There are hundreds of lands out there probably even thousands that can be transferred. Now, each one perhaps might have its own special set of challenges, but this is definitely one model and there's a lot of volume to it.

Angela Glover Blackwell: 20:27

Jeff, what does it feel like when you realize this was actually going to happen and it was gonna happen on your watch?

Jeff Darlington: 20:35

Well , I'm still pinching myself, you know, we're , we're not done yet, but we're, we're very much, you know, 90, 95% of the way there. Just have belief and faith in your community, that there are things that bring us together. And I believe that land is, is one of them. It , it can be frustrating and it can be draining to experience the divisions that we have in our society. You know, I've fell victim to that and have had periods of time. When I, you know, question like, can we all work together, but , um, a project like this really reminds you that , uh , we all have some shared values. It does not matter who you are, where you live. You rely on this planet and it's in every one of us to love this earth. So I really am seeing that in , in our community, through our work, at the land trust and through our work with the tribe.

Angela Glover Blackwell: 21:31

Jeff Darlington, thank you so much .

Jeff Darlington: 21:33

My pleasure. Thanks for having me .

Angela Glover Blackwell: 21:44

Jeff Darlington is the Director of the Placer Land Trust, which recently returned plot of publicly owned land to the Colfax-Todds Valley Consolidated Tribe. This conversation makes it clear that returning land to indigenous communities is the moral thing to do. And it is the way to achieve critical environmental goals. Native communities have profound knowledge and wisdom about living in harmony with the land. They're deep ancestral teachings are the antithesis of the mindset of extraction and exploitation that is destroying the environment. Their traditions lean into justice, fairness and reverence for our most precious resources, nature and people. The partnership between theColfax-Todds Valley Consolidated Tribe, and the Placer Land Trust underscores the necessity of solidarity in its transformative power. Let it be a model . Radical Imagination was produced for PolicyLink by Futuro Studios. The Futuro team includes Marlon Bishop, Andreas Caballero, Joaquin Cotler, Stephanie Lebow, Juan Diego Ramirez, Liliana Ruiz, Sophia Lowe , Susanna Kemp and Andy Bosnack. The PolicyLink team includes Glenda Johnson, Vanice Dunn , Ferchil Ramos, Fran Smith, Loren Madden, Perfecta Oxholm and Eugene Chan. Our theme music was composed by Taka Yusuzawa and Alex Sugira. I'm your host, Angela Glover Blackwell. Join us again next time. And in the meantime, you can find us at radicalimagination .us . Remember to subscribe and share. Next time on radical imagination. Land justice with Kavon Ward.

Speaker 5: 23:59

This area was owned by Black folk, and now I need to figure out how I can use, you know, my experience, my passion, and my power to , um, get the land back to the family.

Angela Glover Blackwell: 24:12

That's next time on Radical imagination.

Clyde Prout III served his tribal council since 2009, and became the tribal chairman for Colfax Todds Valley Consolidated Tribe in March of 2016. His goal as tribal chairman was to focus on the betterment of the tribal community and bring awareness of the tribal community to Placer County.

His family (Prout, Suehead, Gilbert, Dick) has inhabited Placer and Nevada Counties for generations. They descended from the historic Nisenan (Southern Maidu) and Miwok people of the area. He takes deep pride in his family and the history of his people. "It is important to me to preserve and protect the culture and heritage of where I come from."

Jeff Darlington

Hired in May 2002, Jeff is the first Executive Director of Placer Land Trust and has dramatically increased the pace of land conservation in Placer County. During his tenure Placer Land Trust has completed 60 projects permanently protecting 12,000 acres.

Jeff’s great-grandparents settled in Penryn in the 1920s and his family has been here in Placer County ever since. He grew up in Auburn and now lives in Loomis with his sons. Jeff is a graduate of Placer High School and has a B.A. in History with a Minor in Geography from the University of California, Berkeley. He is a Senior Fellow of the American Leadership Forum, and a member and Past President of the Sierra Cascade Land Trust Council.

“I feel honored to spend my days working to protect the wonderful landscape of Placer County, a place where I have fond memories of growing up. Many of the places where I used to hike or fish are now sadly diminished, or even paved over. But through Placer Land Trust we have the opportunity to save the beautiful natural areas and working farms and ranches that together make this County such a wonderful place to live.”

Placer Land Trust’s land acknowledgment seems relevant background info for this podcast:

The protected lands in Placer Land Trust’s care are the ancestral lands of the Maidu, Miwok, Nisenan and Washoe tribes. These lands were forcibly seized, and these tribes were unjustly treated. Although Placer Land Trust cannot change the past, we seek to work with local Native American tribes where we can to help address this injustice.